In this 3-5 lesson, students will examine comic strips as a form of fiction and nonfiction communication. Students will create original comic strips to convey mathematical concepts.

National Core Arts Standards National Core Arts Standards

VA:Cr1.2.3a Apply knowledge of available resources, tools, and technologies to investigate personal ideas through the art-making process.

VA:Cr1.2.4a Collaboratively set goals and create artwork that is meaningful and has purpose to the makers.

VA:Cr1.2.5a Identify and demonstrate diverse methods of artistic investigation to choose an approach for beginning a work of art.

Common Core State Standards Common Core State Standards

ELA-LITERACY.W.3.2 Write informative/explanatory texts to examine a topic and convey ideas and information clearly.

ELA-LITERACY.W.4.2 Write informative/explanatory texts to examine a topic and convey ideas and information clearly.

ELA-LITERACY.W.5.2 Write informative/explanatory texts to examine a topic and convey ideas and information clearly.

MATH.CONTENT.3.MD.A.2 Measure and estimate liquid volumes and masses of objects using standard units of grams (g), kilograms (kg), and liters (l).1 Add, subtract, multiply, or divide to solve one-step word problems involving masses or volumes that are given in the same units, e.g., by using drawings (such as a beaker with a measurement scale) to represent the problem.

MATH.CONTENT.4.MD.A.1 Know relative sizes of measurement units within one system of units including km, m, cm; kg, g; lb, oz.; l, ml; hr, min, sec. Within a single system of measurement, express measurements in a larger unit in terms of a smaller unit. Record measurement equivalents in a two-column table.

MATH.CONTENT.5.MD.A.1 Convert among different-sized standard measurement units within a given measurement system (e.g., convert 5 cm to 0.05 m), and use these conversions in solving multi-step, real world problems.

Editable Documents : Before sharing these resources with students, you must first save them to your Google account by opening them, and selecting “Make a copy” from the File menu. Check out Sharing Tips or Instructional Benefits when implementing Google Docs and Google Slides with students.

Videos

Websites

Additional Materials

Teachers should review the lesson and standards. Math standards are suggested but not limited to the ones listed. Visit CCSS Math Standards for more information. Review the book, Comic Strips: Create Your Own Comic Strips from Start to Finish by Art Roche. Select a video from the Peanuts Collection or Snoopy Collection (example: Peanuts Independence Day ). Exploring the following resources is also helpful prior to teaching the lesson: Early Peanuts Comics Strips (1950-1968), age-appropriate comic strips , an example Math Comic Strip , the history of comic strips, and parts of a story.

Students should be familiar with grade-level math and parts of a story (setting, characters, plot).

Adapt math materials as needed and allow extra time for task completion.

There’s no need to divide critical thinking from creativity. The two easily meld into classroom activities with art as the starting point.

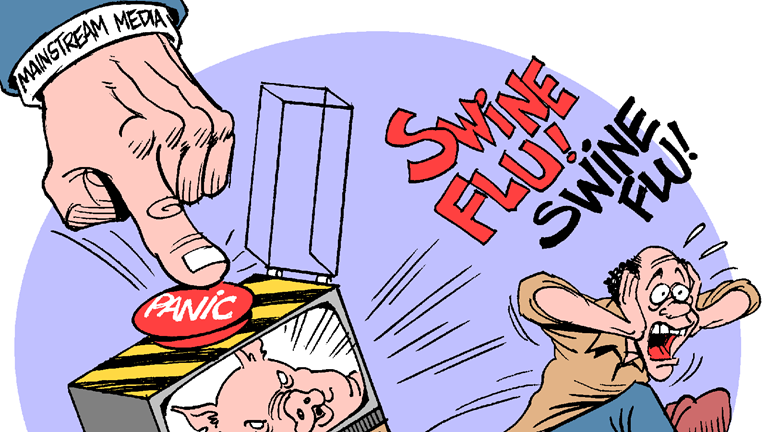

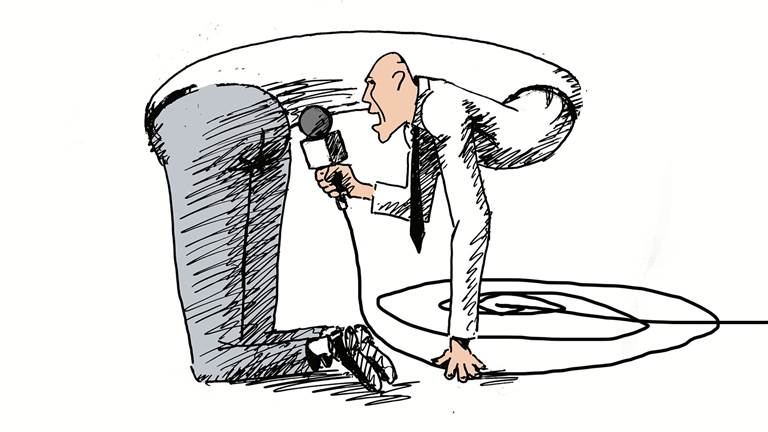

In this 6-8 lesson, students will examine political cartoons and discuss freedom of speech. They will gather and organize information about a current or past issue that makes a political or social statement and analyze the different sides. Students will plan, design, and illustrate a political cartoon that presents a position on a political or social issue.

In this 9-12 lesson, students will analyze cartoon drawings to create an original political cartoon based on current events. Students will apply both factual knowledge and interpretive skills to determine the values, conflicts, and important issues reflected in political cartoons.

In this 6-8 lesson, students will examine the influence of advertising from past and present-day products. Students apply design principles to illustrate a product with background and foreground. This is the first lesson designed to accompany the media awareness unit.

Middle school math teachers will unlock students’ “artistic mathematical eye” with arts objectives, lesson openings, essential questions, and student choice.

In this 3-5 lesson, students will clap rhythm sequences and compose an eight-measure composition. Students will explore rhythm concepts, including the names and symbols associated with music notation. They will also compare rhythmic sequences to math concepts.

In this 3-5 lesson, students will infer the moral of a story and compare two mediums of Aesop’s fable, “The Crow and the Pitcher.” Each student will design their own puppet to act out the fable using pebbles and water in containers. Students will make predictions about Crow’s strategy then make comparisons with their findings.

In this K-2 lesson, students will construct patterns using visual arts designs and math manipulatives. They will identify patterns existing in the natural and man-made world, art, math, and science.

Eric Friedman

Director, Digital Learning

Kenny Neal

Manager, Digital Education Resources

Tiffany A. Bryant

Manager, Operations and Audience Engagement

Joanna McKee

Program Coordinator, Digital Learning

JoDee Scissors

Content Specialist, Digital Learning

Caroline Gage

Intern, Digital Learning

Generous support for educational programs at the Kennedy Center is provided by the U.S. Department of Education. The content of these programs may have been developed under a grant from the U.S. Department of Education but does not necessarily represent the policy of the U.S. Department of Education. You should not assume endorsement by the federal government.

Gifts and grants to educational programs at the Kennedy Center are provided by A. James & Alice B. Clark Foundation; Annenberg Foundation; the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation; Bank of America; Bender Foundation, Inc.; Capital One; Carter and Melissa Cafritz Trust; Carnegie Corporation of New York; DC Commission on the Arts and Humanities; Estée Lauder; Exelon; Flocabulary; Harman Family Foundation; The Hearst Foundations; the Herb Alpert Foundation; the Howard and Geraldine Polinger Family Foundation; William R. Kenan, Jr. Charitable Trust; the Kimsey Endowment; The King-White Family Foundation and Dr. J. Douglas White; Laird Norton Family Foundation; Little Kids Rock; Lois and Richard England Family Foundation; Dr. Gary Mather and Ms. Christina Co Mather; Dr. Gerald and Paula McNichols Foundation; The Morningstar Foundation;

The Morris and Gwendolyn Cafritz Foundation; Music Theatre International; Myra and Leura Younker Endowment Fund; the National Endowment for the Arts; Newman’s Own Foundation; Nordstrom; Park Foundation, Inc.; Paul M. Angell Family Foundation; The Irene Pollin Audience Development and Community Engagement Initiatives; Prince Charitable Trusts; Soundtrap; The Harold and Mimi Steinberg Charitable Trust; Rosemary Kennedy Education Fund; The Embassy of the United Arab Emirates; UnitedHealth Group; The Victory Foundation; The Volgenau Foundation; Volkswagen Group of America; Dennis & Phyllis Washington; and Wells Fargo. Additional support is provided by the National Committee for the Performing Arts.

Social perspectives and language used to describe diverse cultures, identities, experiences, and historical context or significance may have changed since this resource was produced. Kennedy Center Education is committed to reviewing and updating our content to address these changes. If you have specific feedback, recommendations, or concerns, please contact us at [email protected] .